THE HOUNSKULL.

It is entirely commonplace for an object to carry with it a strong association with some time or place or event. Even a feeling can be summoned up by the most unlikely of articles.

I possess a pair of black leather gloves of the finest quality, which I bought in Paris, in the summer of 1892, some years ago now. They are precious to me and for that reason I wear them rarely, but they never fail to return me, in my mind, to that most exquisite of cities. To slip them on takes me back to a gentle autumn, many years ago, to a time and a place where I was awakened to beauty, elegance and a carefree joie- de- vivre that left a lasting impression upon me. Those feelings and recollections must have been intense to have lasted for so long and to be so vividly recalled just by slipping on a glove but would another person putting on those gloves have felt the same experience? I think it highly unlikely.

But can feelings or events actually leave an imprint which can be passed on to someone who has had nothing to do with the original happening?

I recently visited an old friend, The Reverend K. A widower in his fifties, he and his two delightful daughters, both in their early twenties, lived in a small parish in rural Oxfordshire. His charming home, in a tranquil community, had always basked in the warmth of a happy family life and one would have thought that he was as snug as my hand in one of those beautiful leather gloves - and so he was, to all appearances. And yet there was an ominous, although undefined, note of anxiety in the letter to me from the elder daughter, Ruth, which almost begged me to write to her father with some pretext to visit their home.

This was easily arranged and within a couple of weeks I was alighting from a cab at the end of the vicarage drive, carrying a bag to last me for a few days' stay and a parcel of title deeds to go through with clients who lived no great number of miles away. My welcome was typically warm from all members of the household but there were hints of relief and gratitude in the demeanour of the girls.

My friend K was a mild, almost timid man. He would do anything to avoid a quarrel and even gentle debate would tinge his peaceable disposition with anxiety. I never did understand how it was, then, that his hobby, or should I say interest, no, those words don't carry enough intensity, his passion in life was medieval armour and weaponry. Warfare has never particularly attracted me; it has always seemed terribly wasteful of material, life and effort. And of all battles, those of the Middle Ages, with their armour- clad knights on horseback, represent to me not nobility but the embodiment of clumsy, unsubtle brutality.

But this gentle soul was entirely preoccupied with his collection of breastplates and chain mail, pieces of armour fashioned to prevent hideous injury and cruel swords, knives and other bits of steel designed to cause the same. It was the most extraordinary contradiction, but one which had stood the test of time, for he had always, since we were friends as young men, been irresistibly drawn to this subject.

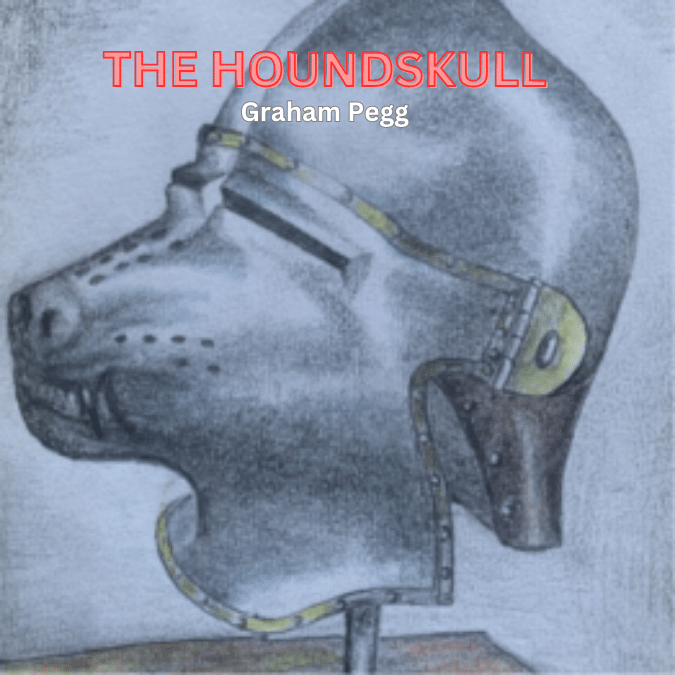

There was little time for Ruth or her sister to explain the reason for their concern. In a snatch of conversation while K was out of the room Ruth referred to a new addition to his collection of armour, but it made little sense to me. Over dinner my old friend began to enthuse over a fifteenth century helmet he had chanced upon in a collection in Colchester while, ironically, visiting on Church business. This piece, no doubt the item to which Ruth referred, was, apparently, called a Hounskull, which means it had a pointed visor, fitted to an open-faced helmet, called a basinet. The visor is hinged so that it can be raised over the top of the helmet to allow the contraption to be taken on and off. But this visor was fashioned to look like the nose or muzzle of an animal - a wolf or a dog, I could not decide exactly which animal it was supposed to be, once I eventually saw it, but it produced an effect which was, most emphatically, horrifying.

After the first hour of description of the object, its purchase, its design, (possibly Flemish - K had deduced) and of its elaborate and ornate construction, during a dinner that was otherwise delightful, I was heartily bored but could not see why the daughters were so anxious for me to experience all this. I did, however, detect just a hint of some guilty secret that K was not telling me. There was the merest trace of furtiveness, a nervous licking of the lips and a sly look around before the next enthusiastic outpouring, which rang distant, warning bells. All of this before I had actually been presented before the object of so much excitement, an experience which my dear old friend's impatience was too strong to postpone any further than the main course, - we never got to the dessert, much to my disappointment, and we went to the armour room.

How strange to find, in the home of a gentle, white-haired cleric, a room crammed with the instruments of brutal death. A sword may be a beautifully worked piece of art, but it is a weapon designed to kill, and most medieval swords were designed not to pierce like the later rapier, but to hack and dismember. The litter of gauntlets, breastplates, helmets and other pieces strewn about the room gave the impression of scattered, broken, metal body parts over which a few intact or virtually intact suits of armour stood guard.

But on its own table, in the centre of the room, exuding a far deeper menace, was the Hounskull. The purpose of its design was horribly clear. It was to protect the wearer and its strength was obvious, but it was also meant to instil fear and horror, which it did in full measure. Just in that room it managed to combine the worst of human and animal with something more sinister than both. It conveyed a powerful impression of evil and of brutality. In the decoration of the snout there was a suggestion that beneath the steel skin there were large teeth and was that the hint of a smile on that ugly, diabolical face?

Meanwhile K prattled on about the features that he had used to date this thing, and what battles it might have been worn in. That it had seen active service was beyond doubt as it had a number of nasty looking scores, dents and gouges. He seemed very certain that it had been used in the Low Countries, indeed he expressed this as a fact not an opinion and, at first, I puzzled as to how he could be so sure. But I soon learned.

"Whenever I put it on???" he said, and I stopped him, appalled. Logically there was no reason why he should not try it on, but the idea horrified me. He explained that all collectors will try on what they purchase, and I tried to accept that rather obvious fact but could not get out of my mind the idea that with that thing on his head it would not be K - it would be someone else. A stupid notion, of course, but the dear chap tried to be sweetly reassuring and said that he definitely remained himself. It seemed though that my flight of fancy gave him the courage to continue, perhaps with fuller frankness, the account that he had started.

Whenever he put it on, he said, he was able to imagine, with amazing clarity, actual events in which the helmet had been used. He said it was like being inside a picture book but one where the pages turned themselves. He described in great detail being the wearer of the helmet in the great hall of a castle, trying on armour, then later being hoisted by some mechanical contraption onto the back of a horse and galloping off. On another occasion he was apparently at a tournament, and he described in vivid detail the crowds, the pavilions, the jousting and even snatches of conversation that he heard. Yes, he could hear as well as see; he even remarked on the smell of the horses, and of the food that was cooking to feed the crowds.

As he spoke his face was radiant with excitement and his eyes blazed. It made me recall a thought that had half formed in my mind over dinner, namely that K looked very tired and overwrought. But not now; his enthusiasm took years off him. I wanted to tell him that I found the whole business very alarming and unnatural, indeed I tried to but, with great gentleness, he told me that I must be tired and that it was very wrong of him to keep me up so late after my journey and that I must be longing for my bed. I was, but not so tired that I did not note that K, after bidding me goodnight outside the armour room, went back inside.

I often sleep fitfully on my first night in a strange bed, and I did that night. At one point I awoke and could have sworn I heard a great shout from downstairs but having sat up in bed, I waited to see if it recurred, as only then is one certain that one has not been dreaming, and as there was no further noise of any kind at last, I drifted off again.

I confess to having had a feeling of relief, on entering the dining room at breakfast time, to see the back of my old friend as he helped himself from the sideboard. Relief became dismay as he turned to face me. His face was haggard and grey, his hair lank and unkempt, his clothing dishevelled. I accused him of putting the Hounskull on again and he did not deny it - he simply sat and put his head in his hands. I asked the daughters to send a telegram from the village to my clients to defer my visit for a day and resolved to have a long talk with my dear old friend. In that I met no opposition, and I was soon sitting in a sunny drawing room listening to a description of last night's experience.

K had paced up and down in the armour room, after I had gone to bed. He had been debating with himself whether he should ever put the helmet on again. At last, he said, he could not resist the impulse any longer. This time he was taken to a scene just before dawn. He told me that he was again on horseback, in a line of men, most of whom were on foot but still heavily armoured, entering a burning village. There was the unmistakable noise of battle some distance away beyond the village and the column was making for that sound. The landscape, still dark, was lit by numerous fires and by the first streaks of dawn in the sky. Bodies, both human and animal, lay everywhere. The stench of death and burning filled the air. He described how from each tree in an avenue through the centre of the village there hung at least one body, all hideously hacked and disfigured, mostly dead but some expiring in torment with tattered pieces of clothing, armour and limbs hanging gruesomely down. The first shafts of light from a blood red sun completed the vision of a passage into Hell.

What seemed to distress poor K as much as this picture was the way he felt about his situation, while wearing the Hounskull,. He told me that his heart beat fiercely and there was some apprehension at the impending battle but that instead of horror and repugnance at his surroundings and at what he was about to join, he felt only elation.

Beyond the last blazing cottage came a slight crest at which the column paused to take in the view. They gazed down into a shallow bowl in the landscape into which, from all sides, men in armour were streaming, looking from a distance like row after row of beetles hurrying down to join hundreds of others writhing and wrestling with each other in the centre. The mounted knights went to the front of the column and together they rode down into the battle, deafened now by the roars and screams from below, followed by the troops on foot. K described the crash as the riders met the edge of the battle, scattering friend and foe alike and driving on, with lances straight before them, into the melee, trampling under the horses' hooves everyone and everything in their way. Once the impetus of the charge had gone and all the lances were shattered or dropped, swords and axes were drawn, and K described the process of slashing and hacking at every living thing within his reach. He spoke of a fallen enemy knight, who managed to stand and swing his sword skilfully enough for it to crash against K's shield and breastplate, only for K to return the compliment with a blow from his axe between shoulder and neck, which nearly decapitated him. He described his exaltation at delivering this bone-crunching blow and as the knight fell, K's own foot soldiers reaching the spot, swarming over the dying man and finally despatching him.

As his description of the battle drew to a close, he explained that he had suddenly felt able ("freed" I think was the word he used) to remove the helmet and that having done so he almost passed out with exhaustion and that he had spent the rest of the night in fitful sleep in the armchair in the armour room. I tried to gently advise him that he should get rid of this awful object, but he became so animated and distressed at this that I relented and tried to reach an agreement that he should not put it on for the time being, at least, not (he added - as this was not at all my idea) without me being present.

But he was like a drunkard, promising to renounce his drink, knowing that it was just a matter of time before he took up the bottle again. That afternoon Ruth came to me as I sat reading in the drawing room and told me that she had seen her father go into the armour room again. I raced in only to see him sitting in the armchair, but bolt upright, with that ghastly helmet firmly on his head. I shouted out to him, and he acknowledged me, by name, and began to narrate his vision.

He was with a large group of knights, riding to meet an enemy that was awaiting them at the foot of a slope. There was much surprise and jocularity that the enemy had been caught in such unpromising terrain. Their forces would be swept away by the speed of the knights on horseback charging down that hill. They gathered speed and confidence roaring with excitement and anticipation. But suddenly K's demeanour changed. The leading knights fell, as did row after row of them, falling into a ten-foot-wide trench, dug deep into the sandy soil of the hill which the slope had concealed until it was too late. Those who saw the trench simply could not stop, driven on by the press of riders behind. Horses fell, trapping and maiming riders who were themselves fallen on and crushed by others. Those few who managed to clamber through had lost all speed and were cut down by crossbowmen. K described making the decision to try to ride across the bodies of the foremost knights and horses as they lay screaming and dying. But his horse stumbled and threw him onto the far bank of the ditch, where he tried to clamber to his feet as crossbow bolts thudded into his shield, a few piercing his armour.

I had had enough at this point, and I called for Ruth to help me remove the helmet. As K thrashed about and described enemy soldiers swarming over him, she and I struggled with the visor, not at all helped by her father's flailing arms. He screamed out "they have knives, - they are trying to take off my helm?." just as we managed the task and the old man gave a final cry, clutched his throat and fell back in the chair. Whether in his mind he died in his armchair at home or on a hillside battlefield we will never know but he lasted only seconds after the Hounskull was removed. Should we have left it on him? I really cannot say. I fail to see how it would have improved his chances of living through whatever he was experiencing but it is not pleasant to recollect that this was immediately followed by K's death.

The daughters begged me to get the Hounskull out of their home and so, after all the formalities were completed and I felt able to take my regretful leave of them, I took the thing away and, for want of any better thing to do, I put it on a table in the corner of my study. It sits there now.

It seems to be looking at me.

As I examine it here, I have to concede that beneath the patina of age, and despite the dents and scratches there is quite extraordinary workmanship in it. It is covered in the finest and most subtle engraving. One has to admire the craftsmanship with which the muzzle is formed, clearly conveying a hint of a snarl and powerful teeth underneath. The eye slits, mere empty spaces, nevertheless give the impression of a creature which, while far from benign, is capable of intelligent thought. Why am I bothering to study it so?

Would it have the same effect on me if I put it on? A foolish thought, and yet strangely compelling. Surely, if I left it with the visor up, I could snatch it off at the first hint of trouble.

I will try it, just once, tonight.