As the long bell rang, Basava jolted upright, startled awake. For nearly an hour, he hadn't stirred despite the booming voice of K.D. Master, who was teaching about thunder and lightning with the same intensity as the storm itself. But the bell snapped him out of his slumber - a fact only the boys at the front desk noticed, as no one else did. Known for his dramatic antics, the science teacher, K. Devaraju, had earned the nickname "K.D." (short for "Kedi," or troublemaker) among the students. Basava, who usually sat at the front for every class, always slipped to the back bench for K.D.'s lessons. Today, his empty stomach - unfed since morning - and the headmistress's stern warning not to return to class without paying fees by tomorrow had left him exhausted. So, slumped in the back, one hand clutching his growling stomach as if to quiet it, he'd dozed off. With over a hundred boys in the class, there was little chance of catching K.D.'s eye.

The other boys shouted "Hooray!" and rushed outside. When Basava tried to stand, his legs wobbled. The headmistress's words echoed in his mind: "If you can't afford it, you should've gone to some government school." Her words stung, and he recalled his unspoken retort: "Why? Can't poor kids study in a good school?" Unable to voice that question then, he now felt a pang of regret. Mustering his strength, he slung his bag over his shoulder and shuffled out. As he stepped into the corridor, he nearly bumped into Anita Miss, the Kannada teacher. Noticing his sluggish walk, she asked, "Basava, are you okay? You look like you've been sleeping." Basava was stunned. K.D. Master didn't even notice I was asleep! How does Anita Miss know? he wondered. Before he could think, he blurted, "No, Miss, I'm just hungry," then quickly added, "I mean, nothing's wrong, Miss," in the same breath. Without a moment's hesitation, Anita said, "Wait here, I'll be right back," and hurried toward the staff room.

Just then, K.D. Master emerged from the same room, washing chalk dust off his hands. Spotting Basava, he barked, "Hey, poor boy, why didn't you come to my class?" Trembling, Basava stammered, "No, sir, I was there, sir. I heard your thunder and lightning lesson, sir." K.D., who'd already forgotten his own question, gave Basava a look as if he were some strange creature and walked off. At that moment, Anita Miss returned, holding out a half-empty packet of biscuits and a five-rupee note. "Here, take these. Eat the biscuits and get some coffee or tea somewhere," she said warmly. As Basava took them, he looked up at her with gratitude, almost bowing. She gently patted his head, smiled, and walked away. This wasn't the first time Anita Miss had helped him. Once or twice a week, she'd call him over to share snacks, sometimes even inviting him to her home to eat. She'd given him notebooks and comic books to read, too. But unlike K.D. Master, who called him "poor boy," or the headmistress, who labeled him "good-for-nothing," Anita Miss never belittled him.

Basava watched her until she disappeared from view. A thought struck him: Anita Miss must be God. She knows when I'm asleep. She knows when I make mistakes in lessons. She knows when I'm hungry. Amma says God knows everything. His heart warmed as he thought of his mother and little sister, Putti. Clutching the biscuits, he headed home. He didn't feel like eating them yet. I'll share them with Putti. She must be hungry too, he thought. That morning, there'd been nothing to eat at home, and his mother had said, "Come back from school, and I'll have something ready." Remembering her words, he quickened his pace, breaking into a run.

***

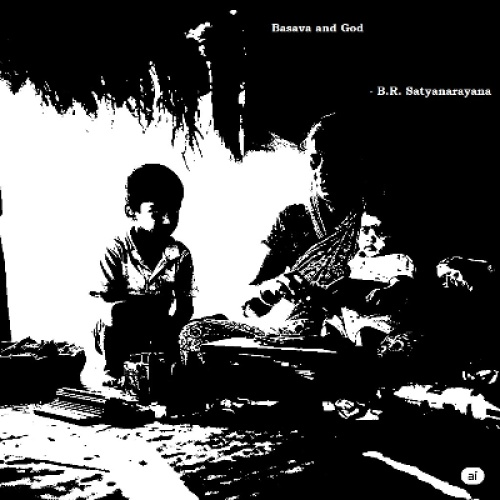

When Basava reached home, the familiar sight greeted him. His mother sat by the door, legs stretched out, rolling beedis. Beside her was a mortar with tobacco leaves and cut Tendu (Diospyros melanoxylon) leaves. Putti lay across her lap, playfully holding a Tendu leaf. "Putti, your brother's here! Get up and make something for his stomach," his mother said, starting to rise. Basava stopped her. "Amma, Anita Miss gave me biscuits. We'll eat those now and have food later." Putti ran to him, asking, "Anna, will you give me some?" Lifting her up, Basava grinned, "I brought them all this way just for you!" He opened the packet, gave her two biscuits, and took two for himself, finishing them quickly. As the last bite went down, the headmistress's warning crept back: "If you don't pay the fees tomorrow, don't come to class." Turning to his mother, he said, "Amma, the headmistress said if I don't pay the fees tomorrow, I can't go to school." He looked at her face, waiting for a response. She glanced at him briefly, then returned to her beedis. Hesitantly, he added, "Amma, with fines, it's a hundred and five rupees for two months."

This time, she spoke, her voice heavy. "Basava, what can I do? We don't even have three grains of rice at home. Your father drinks away every paisa. If he doesn't come home drunk tonight, maybe we can scrape together enough for the fees." She paused her work, stood, and said, "Wait, let's see." She brought a basket of rolled beedis and poured them onto the floor. "Count these, Basava. If we're lucky, we might manage the fees somehow." As Basava counted, the pile dwindled before reaching three hundred beedis. "Amma, it's three hundred beedis," he said. She sighed, "That's about eighty rupees. What can we do with twenty-five rupees short? If your father comes home drunk tonight, what then?" She began packing the beedis into a sack.

Basava, watching her, remembered the five-rupee note in his pocket. "Amma, Anita Miss gave me five rupees for coffee. If we add that, it's eighty rupees. We still need twenty." His mother nodded, "Alright, we'll see. Now go study in the shade." She returned to her beedis.

Basava opened his science notebook, starting on K.D.'s thunder-and-lightning lesson. But soon, Anita Miss filled his thoughts. Closing the book, he picked up his Kannada textbook and began reciting a poem aloud: "Walk forward, walk forward, neither shrinking nor faltering, walk forward." He stopped, struck by how beautiful Anita's name was. What does Anita mean? he wondered. It felt like a god's name. My name, Basava, means bull. Who named me that? Turning to his mother, he asked, "Amma, who named me Basava?"

She paused, surprised he'd stopped studying to ponder this. After a moment, she said, "Who else? Your uncle named you after Basavanna, the saint who saw God in everyone. He wanted you to be like him, so he enrolled you in school." Basava knew his uncle had passed away, but this was new. "Amma, my uncle got me into school?" he asked. "Yes," she replied, wiping her eyes. "He wanted you to study well, but God took him early. Before he died, he made me promise to keep you in school, no matter what. That's why I work day and night to make sure you study."

Basava sat quietly, picturing his uncle from childhood memories. Why didn't he name Putti? he wondered, then realized his uncle had died before Putti was born. "Amma, why haven't we named Putti yet?" he asked. "What's the rush? We'll give her a name someday. Now study," she said. But Basava insisted, "No, Amma, that won't do. My sister needs a proper name. I'll give her a good one myself." He picked up his book again.

As dusk fell and the letters blurred, his father stumbled home. The stench of liquor hit before he did. Leaning against the wall, he began shouting. Putti, frightened, clung to Basava's hand. Their mother, as if oblivious, grabbed the beedi sack and stepped out. Basava, holding Putti's hand, followed her.

***

The next morning, as Basava left for school, his mother handed him eighty rupees, including the five-rupee note. "Tell your headmistress this is all we have. We'll pay the remaining twenty-five rupees next week, somehow," she said. Basava didn't know what to say. To Putti, he said, "It's Saturday, I'll be back early. We'll play!" Slinging his bag over his shoulder, he left. His mother's faint "Be careful" trailed behind him.

At school, wanting to settle the fees before prayers, Basava rushed to the headmistress's room. Standing with hands clasped, he said in one breath, "Miss, Amma said we only have eighty rupees now. She'll pay the rest next week." He pulled the notes from his pocket and held them out. Without glancing at his hand, the headmistress roared, "What is this, a vegetable market where you pay today and tomorrow? Get out! If you are not allowed to go to class for four days, your mother will learn her lesson. If you're so useless, go and die in a government school instead of eating my head here. Here I deal with you lot, there with management, and at home with my husband and kids!" Her voice shook the room's tiles. Basava's legs trembled, but his tongue froze. He wanted to shout, I brought eighty rupees, not ten! but couldn't.

Just then, Anita Miss appeared at the door, asking, "What's this?" Emboldened, Basava repeated, "Miss, I need to pay a hundred and five rupees. Amma gave eighty rupees and said she'll pay the rest next week." The headmistress glared. "Look, Anita, he hasn't paid for two months. When asked, it's always 'this much today, that much tomorrow.' If they can't pay, why struggle in a private school?" Anita didn't respond to her. Turning to Basava, she said, "Give me whatever money you have." As she counted the notes, she noticed the five-rupee note she'd given him yesterday. Facing the headmistress, she said, "Look, Madam, yesterday this boy came to school without eating. I gave him five rupees to buy food. See, it's the same note. He didn't spend it, and his mother somehow managed to scrape together eighty rupees for the fees. Such poverty, yet they want their son to study. They carry loads at the bus stand and roll beedis to send him here. If people like you discourage kids like this, how will they succeed?" With that, she stormed out.

Basava, absorbing her words, didn't know what to do. He was too scared to look at the headmistress. Should I stay or run? he wondered, caught in a moment of confusion. Then Anita Miss returned, handed the headmistress a hundred and five rupees, and said, "Here, Madam, Basava's fees." Taking Basava's hand, she led him out.

***

That afternoon, Basava waited eagerly for the final bell. When it rang, he shot home like an arrow. His mother was rolling beedis, with Putti clinging to her shoulder, swinging playfully. Tossing his bag into a corner, Basava burst out, "Amma, Amma, Anita Miss paid all the fees! She said we don't need to pay the twenty-five rupees. From now on, she and her husband will cover my fees and make sure I study. Her husband came to the school and said I just need to study well!" He said it all in one breath. His mother set aside her beedis, pulled him close, and hugged him. "My heart's at peace, son. I'll do whatever I can. You just study well," she said, wiping tears.

As Putti toddled over, Basava lifted her onto his lap and said, "Amma, let's name Putti 'Anita.' She'll study well like Anita Miss and become a teacher. She'll be like a god, seeing the divine in every child's heart. Right, Amma?" He kissed his sister. "Let it be so," his mother said, kissing Putti too. "From today, Putti is Anita." They didn't even think about lunch that afternoon.